December 2020: Use of force

Home Office statistics show potentially lethal TASER rapidly cementing a place as a tactic for defusing situations

Dear StopWatchers,

Congratulations for getting to the end of what has been an unusually difficult year. Between a global pandemic and Black Lives Matter protests, we’ve experienced some unprecedented upheavals in the ways we are policed. But if one thing has remained the same, it is the police’s desire to find ever more excuses to use stop and search. We have written about how the mission creep of stop and searches risks finding its way into the area protest policing in a significant threat to our civil liberties, as first reported by Netpol.

Elsewhere, we held a workshop with Bristol CopWatch called ‘Who Polices the Police?’ in early December, and hope to follow up with more awareness raising events in the new year. StopWatch volunteer Georgia Edwards provides a brief summary of the workshop below (see ‘Bristol CopWatch event – Who Polices the Police?’).

Other stories are:

Home Office statistics show a racially disproportionate use of force – and also the emergence of the TASER as a tactic for defusing potentially volatile situations

A record of failure – one of the UK’s biggest forces is placed in ‘special measures’ after failing to record one in every four violent crimes reported

‘We’re sorry if you feel our policing’s been racist’ – apologies for racially disproportionate policing are no good if police deny racism plays a factor, and more BAME officers won’t solve the problem either

Police Carols spread good cheer (to no one)

Please enjoy our roundup of stories below.

Statistics show a racially disproportionate use of force

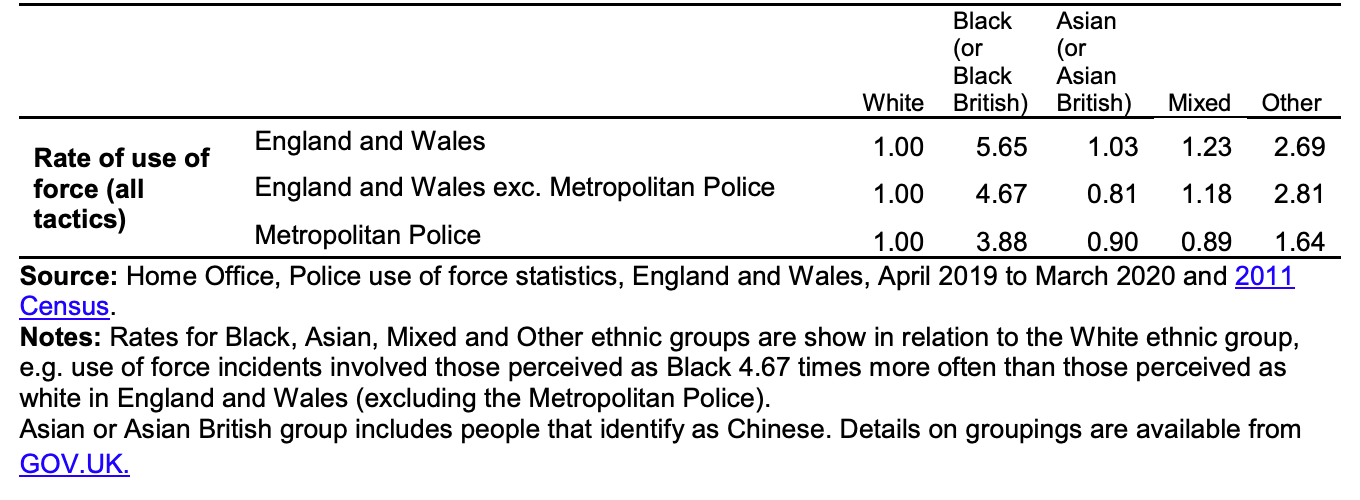

The third annual Police use of force statistics, England and Wales release found that the police used force against Black people ‘five times more frequently’ than against White people in England and Wales in the year to 31 March 2020 (17 Dec, The Independent).

The Home Office report found that:

Use of force tactics, ranging from handcuffing and ground restraint, to the use of batons, Conducted Energy Devices (CEDs) and firearms, involved people perceived as being from a Black ethnic group at a rate five times higher than people perceived as being from a White ethnic group in English and Welsh police force areas (excluding the Metropolitan Police). The rate was almost three times higher for people perceived as being from an Other ethnic group and lower for those perceived as being from an Asian ethnic group.

In the case of lethal weapons – firearms and TASERS® (CEDs) especially – it is important to note that the disproportionality dissipates through each stage of the weapon’s deployment through to being fired. However, the very willingness of police officers across the country to draw lethal instruments on Black people compared with individuals of other ethnicities is a disturbing issue in itself, that some might suspect is at some level driven by questionable perceptions about Black people’s behaviour.

Racial disparities aside though, perhaps the most shocking statistic is the overall comparison from the first recorded year (2017/18): there were over half a million recorded incidents in 2019/20 (508,663), +62% compared with back then (313,137).

Such a rapid increase raises several questions: Have individuals become significantly more violent towards the police in only three years? What happened between March 2017 and March 2020 to make officers see fit to deal with the public more harshly? Or has the use of force been encouraged amidst a climate of mistrust?

One of the most interesting findings is that while restraint tactics represent the majority of instances, TASERS have become the fastest rising use of force tactic: the number of incidents involving them increased +86% in the last three years.

Their increasing prominence chimes perfectly with then home secretary Amber Rudd’s authorisation of police forces to issue the ‘more powerful’ TASER X2 in 2017, and will rise again with the new even more powerful (and less accurate, according to user handling trials) TASER 7 adopted by police forces on current home sec Priti Patel’s say so.

The typical defence of the TASER is that is it never fired in 85% of cases, an indication that ‘the mere presence of its use has been enough to defuse a situation and ensure a peaceful resolution of the incident without any actual force being used.’

Once this justification is made, there really is little stopping the police from fulfilling the dream of LBC radio presenter Nick Ferrari’s tasers for all campaign, which looks more like policing by terror rather than consent.

And the willingness of police officers to rush to draw for their lethal weapons will extend towards children, precisely what the likes of the United Nations have warned against (Guardian, 08 Dec), which has been found to be racially disproportionate too (Guardian, 16 Aug). To quote the National Police Chiefs’ Council independent advisory group on TASERS (NTSAG) earlier this year:

We’ve long said the guidance issued to officers about the justifications for using a TASER is not fit for purpose, as it remains too vague and too open to interpretation.

Under these conditions, the safety many individuals benefit from may become an oppressive one at the hands of a trigger happy officer.

A record of failure

One important fact to remember about use of force records is that they underestimate the true number of incidents involving the use of force on the part of the police. It is understandable that there are natural limitations to recording incidents. However, failing to record one in every four violent crimes reported is inexcusable (Manchester Evening News, 10 Dec):

Greater Manchester Police (GMP) is failing to record one in four violent crimes reported to it, according to a blistering inspection report published today – warning people are being ‘denied justice’.

It also raises serious concerns about GMP’s approach to domestic violence and child protection, as well as delayed, dropped and badly-planned investigations.

The police inspectorate, which had already warned the force about inaccurate crime recording in 2016 and 2018, before criticising its approach to vulnerable victims in 2019, says the situation has since ‘significantly deteriorated’ and has now told the force to address its concerns ‘urgently’.

A week later, Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services announced that they will place GMP in ‘special measures’ (Manchester Evening News, 17 Dec).

Beyond mishandling data, refusal to share it with regulators also damages relations between the public and the police. Take the example of Leon Briggs who died after being restrained by police seven years ago.

His family are finally due to hear his inquest case in the new year (Justice Gap, 18 Dec), but Bedfordshire Police Force have already refused to provide any evidence of their officers’ actions to investigating body the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC), who withdrew gross misconduct proceedings as a result.

Now a six-week inquest will commence on 04 January, and will explore whether the actions of the police were appropriate or whether they contributed to Leon’s death.

What is entirely inappropriate is police force secrecy over officers found guilty of misconduct, demonstrated by Sussex Police’s refusal to tell the public the names of some of the officers kicked out of the force recently (The Argus, 16 Dec). Reporters had to guess popular surnames to find one of the mystery officers, a Patrick George Baker.

Considering this information is available to the public, but only if you know the second name of the officer, The Argus asked the force to provide the names of all 21 officers dismissed since 2017.

But the force has refused, citing privacy.

Unless involved in court proceedings, privacy is an odd defence to make for an individual who formerly served in public office and whose details are on a public database anyway (College of Policing Barred List).

This is why some would prefer the responsibility of scrutiny be taken out of the police’s hands altogether. Police assistant commissioner Rob Beckley is one such person. He proposes that new independent community panels in England and Wales should be given the power to inspect everything police do to root out bias, including their use of force and even where they deploy officers (Guardian, 06 Dec). In his opinion piece he wrote:

Police forces must not control the scrutiny, but hand it over to people who are regarded by communities as independent. It must be mandated across all forces, be entirely random, not limited to stop and search, and also engage the police officers involved.

Transparency and an independent spotlight are the only real routes to constructive change.

That constructive change Beckley writes of still runs at the police’s pace, though. And it feels more obstructive than constructive. For one, we have scrutiny panels in many police force areas already. They can be independent. But do they have the power to compel the police to provide evidence of stops, and if not, how would they obtain such power when in autumn it was reported that the Met Police decided against making body worn footage publicly available?

Secondly, the National Police Chiefs Council, which represents all forces in England and Wales, claims to be working on its own reforms, which may have been what Met Police chief Cressida Dick was referring to when in response to a question from Assembly Member for Hackney, Islington and Waltham Forest Jeannette Arnold OBE over the matter during a plenary meeting, Dick replied that she was ‘open to new ideas, but frankly we’ve got a lot at the moment’.

‘We’re sorry if you feel our policing’s been racist’

Police Service of Northern Ireland chief Simon Byrne issued an apology for his force’s handling of the Black Lives Matter protests in June, after the Police Ombudsman found justification in claims that it was unfair and discriminatory (BBC News Northern Ireland, 22 Dec).

Police Ombudsman Marie Anderson stated that although the 68 fines meted out under COVID-19 regulations were ‘not intentional and not based on race or ethnicity’, it appeared the case that confidence in policing among some in minority communities has been ‘severely damaged’ as a result of the force’s handling of the protests.

In a statement, Mr Byrne said:

We tried our best to respect the public health requirements of the Northern Ireland Executive to save lives and at the same time deal with public outcry triggered by this awful death [of George Floyd].

We operated within the legal framework available to us at the time, but the ombudsman is clear that whilst unintentional, we got that balance procedurally wrong.

It is clear to me that some members of the Black and Minority Ethnic Community have been frustrated, angry and upset by our policing response and our relationship with them has suffered.

For that I am sorry, and I am determined in that regard to put things right.

A disturbing part of the apology and the findings which prompted it is the notion that the police’s actions were ‘not based on race or ethnicity’, a sentiment that chimes with Met Police chief Cressida Dick’s comments last month on the issue of stop and search. It’s an odd defence to make, as Novara Media’s Ash Sarkar identifies in her article ‘The Police Are Going Backwards On Institutional Racism – And Their Most Powerful Officer is In Denial’ (01 Dec), and the grounds upon which it is made are even more odd:

Dame Cressida argued that racial prejudice could not be considered a motivating factor as ‘it wouldn’t be right or lawful’. A curious logic: one would think a serving police officer might be able to entertain the notion that something being wrong or illegal doesn’t preclude it from happening.

Sarkar notes that Dick’s assertion on the subject amount to the argument that racial disparities in stop and search are simply an unfortunate consequence of the overrepresentation of young Black men in criminal activity, Sarkar correctly notes that ‘the expansion of stop and search has not resulted in a proportionate increase in public safety’.

Sarkar then goes on to note that despite the notion that racial disparities in stop and search are simply an unfortunate consequence of the overrepresentation of young Black men in criminal activity, the expansion of stop and search that just happens to focus disproportionately on the unlucky fellas ‘has not resulted in a proportionate increase in public safety’.

It is also worth remembering that in chief Dick’s own area of responsibility, her own officers are less likely to find a blade or firearm on a Black person than a White person.

And this won’t improve with a little more ethnic diversity in the police’s ranks, assuming it’ll ever happen. Former superintendent Leroy Logan – whose career in the police fighting racism ‘from within’ was the focus of an episode of the recent BBC series Small Axe – told Ash Sarkar that the commissioner and the London mayor’s aim of increasing BAME representation to match that of the capital’s resident population (40%) in three years ‘does not make sense’. Logan asked:

It’s taken them 20 years to get to 15%, or thereabouts. So what would make them improve dramatically – by another literally 100% – in three years?

Even if London Metropolitan Police does reach their hallowed target by 2023, having a racially proportionate number of Black officers preside over a racially disproportionate number of stop and searches will not yield the progress the Met Police hopes for. Fairer representation of police officers ≠ fairer policing.

Bristol CopWatch event – Who Polices the Police?

From StopWatch volunteer Georgia Edwards

On 05 December, Neal Brown, our Youth and Engagement Coordinator, held a workshop with Bristol Copwatch, ‘Who Polices the Police?’. Bristol Copwatch is a community project and police monitoring group looking at police brutality, misconduct, and abuses of power in Bristol. It was great to discuss the broader picture of stop and search across the UK with the group, and ways ‘copwatching’ could be used in practice to target disproportionate uses of power from Avon and Somerset police but also forces further afield. It was interesting to think how a method, ‘legal observers’, commonly used by activist groups during protests, could be transferred safely to the streets to support those victim to disproportionate stop and search.

The workshop was around learning what our rights are, the origins of the group, and the value of having a local group to monitor the police and an introduction to Bristol Copwatch and how to get involved. If you live in Bristol or you would like to find out more you can email them at bristolcopwatch@riseup.net.

Section 60 watch*

London

Greenford / Perivale (17 Dec)

Thames Valley Constabulary

Reading (12 Dec), Milton Keynes (18 Dec)

* This is not a comprehensive list

Scrap Section 60 reminder

One to watch: The Private Members’ Bill gets its much-delayed second reading in the House of Commons on 29 January 2021.

Police Carols spread good cheer (to no one)

It’s the time of year to spread good cheer, and a couple of police forces, not wanting to be left out of the season’s celebrations, have provided us with some delightful festive treats.

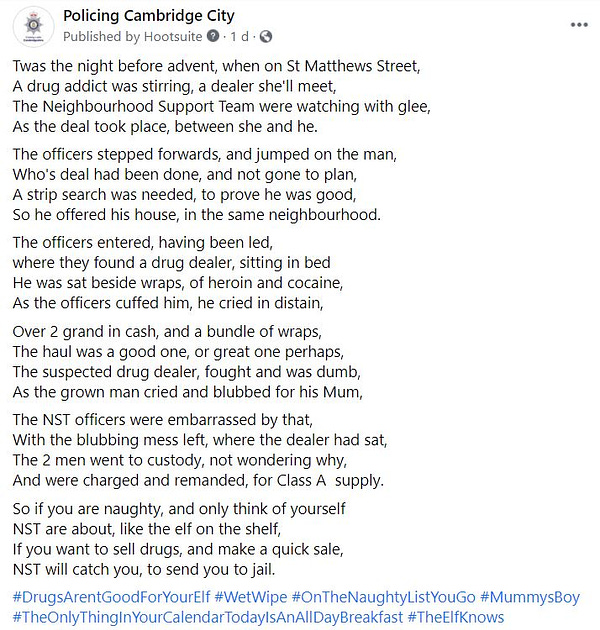

One force went to the trouble of producing a rhyming poem telling the story of how they captured a couple of local drug dealers. Clocking in at six stanzas, Shakespeare would be proud! If we’re being critical, #MummysBoy seems a little harsh, but at least they’ve taken photos to prove they’re doing (their version of) God’s work.

Another force thought it’d a good idea to pack schoolchildren into one of their vans to sing a version of a popular carol warning drug dealers in their area.

Oh come all Craigavon sounds like a viral classic in the making. Strangely, it got deleted from Twitter, but it lives on, thanks to Reddit (also here). You can’t stop a hit!

Don’t say we don’t spoil you. Merry Christmas! 🎄👀🎄

StopWatch is a volunteer led organisation that relies on the generosity of trusts and grant funders to operate. We DO NOT accept funding from the government or police as we believe this would compromise our ability to critically challenge.

As we head into another year, we’d be grateful for any financial assistance you can provide as it helps us become a more sustainable operation. Please feel free to share our GoFundMe page with anyone you feel might be interested making in a one-off donation to our cause. We’d also appreciate regular donations via standing order, if you’d like to pledge your long-term support. Details are:

CAF Bank – Registered office: CAF Bank Ltd, 25 Kings Hill Avenue, Kings Hill, West Malling, Kent, ME19 4JQ

Account Name: StopWatch | Sort Code: 40-52-40 | Account Number: 00027415

—

Stay safe, and have yourself a Merry Christmas and Happy New Year,

StopWatch.