February 2021: Criminalising our way of life

More tales of Met misconduct surface, while the cold streak for wrongful charges brought under the Coronavirus Act continues for yet another month

Dear StopWatchers,

We may be on a roadmap out of lockdown and to a place of safely-vaccinated social mingling with any luck, but the reality for many people living in marginalised communities is that we have never been free from the overzealous gaze of the police, pandemic or not. StopWatch continues to draw attention to the increasing number of ways our ‘law and order’ government wishes to criminalise our way of life.

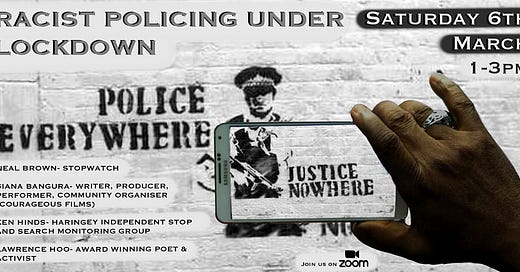

With this in mind, please do join us for a Bristol Copwatch hosted online event Justice Nowhere: Racist Policing Under Lockdown on 09 March, where our Youth and Community Engagement Coordinator, Neal Brown, will give an overview of UK stop and search, and practical information on your rights.

By the way, there’s still time to apply to head up our unit as Executive Director – we’ve extended the deadline for sending in your CV and supporting statement to 22 March. More details are available on our website.

Topics in this newsletter include:

More tales of Met misconduct surface

The cold streak for wrongful charges made in the name of COVID-19 is almost a year old now, with no signs of successful prosecutions happening any time soon

Updates on some of the highest profile cases of deaths from police contact

The two sides of mayor Khan – what Sadiq giveth with one hand, he threatens to remove with another

In Terrible tech, police lies highlight the importance of civilians filming interactions

And we pay tribute to Judge Sir William Macpherson, who headed the Stephen Lawrence inquiry

Please enjoy our roundup of stories below.

More tales of Met misconduct

Following on from last month’s revelations of an inefficient complaints system, a freedom of information request found that only six Metropolitan Police officers have been disciplined over the misuse of stop and search since 2014, out of a total of 5,000 complaints made about officers (BBC News London, 01 Feb).

This seems to give a strong indication that too many police officers in London who conduct stop and searches cannot be trusted to do so properly, but none of this seemed to register with Met deputy commissioner Sir Stephen House, who vowed that the Met would continue to carry out ‘disproportionate’ [newspaper’s air quotes] stop and searches of young black Londoners, because they are in the areas of high crime and violence, ‘where the problem lies’ (London Evening Standard, 01 Feb).

Of course our stopping and searching is disproportionate because if it was proportionate you’d be stopping the same number of people across every single community across London, from north to south to east to west, which is nonsense. We’d be stopping a high number of people in their eighties because there’s a lot of elderly people in London. We don’t do that. We don’t stop and search that many women because they don’t tend to be involved in street violence.

Aside from wildly misunderstanding the meaning of the word ‘disproportionate’, it seems Sir House neither cares nor knows that Black people are also more likely than White people to be stopped in relatively low crime areas too, or that a 2019 BBC Politics London report discovered that despite making up 47% of firearms and 55% of weapons searches in the capital, the Met were less likely than average to find a blade or firearm on Black people.

We wrote that given his track record – curious behaviour surrounding the case of Sheku Bayoh while he was head of Police Scotland, stop and searches of children under 12 years of age long after pledging to abolish them, and attempts to undermine research revealing the industrial levels of stop and search activity on his watch – it would be wise to be wary of his declarations, especially regarding children. Sir House does not seem to be the sort of person who believes they are our future.

A more considered response to disproportionate stop and search numbers for Asians came from Met assistant commissioner Neil Basu, who told Eastern Eye (12 Feb):

Stop and search is the most controversial power that we use. If we cannot explain why it is disproportionate, then we are in a very bad place.

We have to examine it very closely because it is an incredibly valuable policing tool. If we do not use it responsibly and correctly, then we deserve to lose it.

Asians were twice as likely to be stopped and searched than white people in England and Wales, the data revealed. Basu also appealed to young people to advise the police on how to conduct stop and search ‘in a professional and better way’. Recent history of best practice guidance suggests the police have enough advice to be go on already.

Plus, a recent poll from UK charity Revolving Doors Agency provides precisely those pointers that Basu is after from young people (The Justice Gap,15 Feb):

Seven out of 10 young adults think that the police were treat them differently if they come from a deprived area or if they are a person of colour…

The report… found that over half of young adults did not think that the police consistently act in line their own beliefs and values (54%) or would act compassionately towards them (53%). The problem was found to be exacerbated for young adults with mental health needs, disabilities or long-term health conditions.

The survey of 689 young people (aged between 18 and 25 years) suggested that police should develop a common definition of vulnerabilities and train police to identify them, citing ‘low maturity, poverty, structural inequalities, mental health conditions, disabilities and neurodiverse conditions’ as examples.

Still, unlike Sir House, Neil Basu at least appreciates the importance of policing by consent enough to not simply dismiss racial disproportionality concerns:

‘I’m less concerned about it raising a generation of criminals. I’m more concerned about generating a generation that no longer trusts the police. That is bad for the public and bad for society.’

Of course, to get to the roots of the issue of racial disproportionality, we have to identify the cause. But all the detectives in their ranks cannot deduce the obvious fact staring the police in the face (Sky News, 26 Feb). Perhaps this explains why – according to a report from Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services – fewer than one in every ten (9%) of stop and searches are intelligence-led. The report also says that, over 35 years on from the introduction of stop and search legislation, ‘no force fully understands the impact of the use of these powers. Disproportionality persists and no force can satisfactorily explain why.’ Denial is one hell of a drug.

‘Stop making wrongful charges in the name of COVID-19’ challenge

Next month will be a year since the COVID-19 pandemic triggered the UK Government into passing the emergency public health legislation to protect its citizens and by extension, a new wave of overzealous policing.

And in that year, almost a third of all prosecutions brought under coronavirus legislation were incorrect, leading to hundreds of cases being dropped (The Independent, 06 Feb):

A review by the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) found that 359 of 1,252 charges last year under laws brought in to aid public health measures were later withdrawn or quashed in court.

Worse still, every single one of the 232 prosecutions brought under the Coronavirus Act has, to date, been wrongly charged. Every. Single. One.

It would be impossible for our law enforcement agents to be more wrong, except for the fact many more potentially unlawful fines brought under the Act have already been paid by people too afraid to challenge them, as director of Liberty Gracie Bradley pointed out. But while Bradley urged the government to ‘urgently introduce a right to appeal fines’, the government said it has ‘no intention’ of scrapping the law, and Max Hill QC, head of the Crown Prosecution Service said that it would be making no formal recommendations, despite the findings of its review.

Hill QC told The Independent: ‘The Act has a purpose. It’s right that we must point out where there’s been a mistake made and we will continue to do that, but any changes are not for us to recommend and not for us to put into effect.’ But what purpose does the Coronavirus Act have if after almost a year it has been used wrongly 100% of the time? Is it to strike fear in the minds of the public with its arbitrary use and raise levels of mistrust and suspicion of the police?

And what of the harm caused when the police misjudge a situation? Take the incident in Belfast centred on the commemoration of the 1992 loyalist murder of five people at the Sean Graham bookmakers shop (ITV News, 11 Feb).

The Police Ombudsman watchdog has initiated an investigation into how police handled the event, suspending one officer from duty and repositioning another after tensions flared when they approached some of the attendees to highlight potential coronavirus breaches in relation to the size of the gathering.

One attendee to the commemoration, who was shot multiple times in the 1992 attack, was arrested and detained on suspicion of disorderly behaviour, but later released.

Chief constable Simon Byrne has since apologised for how the police handled the incident, claiming ‘the officers involved fell below the expected standards of the PSNI (Police Service of Northern Ireland)’, while the controversy sparked a political row between republicans and unionists. Thankfully, a degree of consensus was reached on this occasion, but things could have been so much worse.

Deaths from police contact, cases old and new

Mohamud Hassan

New information has come to light regarding the circumstances of Mohamud Hassan’s death, revealing that from the time Hassan was taken into custody to his release, he came into contact with ‘50 plus police officers’ (Guardian, 09 Feb).

Then investigators from the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) served a misconduct notice on a South Wales Police officer on Monday (IOPC, 15 Feb). This is in part down to the pressure that Hassan’s family have put on South Wales Police and the IOPC to come clean about what really happened. Follow the family’s campaign for justice here.

Leon Briggs

In the inquest of Leon Briggs, the lawyer representing his family, Dexter Dias QC, accused acting sergeant Loren Short of telling the jury ‘a pack of lies’ about his and fellow officers’ actions in the run up to his death (BBC News Beds, Herts & Bucks, 02 Feb).

The jury also heard that Short provided prepared statements about the incident which were ‘exactly the same’ as colleague constable Geoffrey Bennett, and that the acting sergeant answered ‘no comment’ to ‘virtually every single question’ in four different interviews about the incident. Short denied lying and said the restraint was necessary. The inquest continues.

Kevin Clarke

Three years on from his death following restraint by police during a mental health crisis, Kevin Clarke’s family and INQUEST are to host an online memorial event on 09 March, in which there will be discussions about the circumstances and impact of his death, the wider context of racism in policing and the Black Lives Matter Movement, and how you can support Kevin's and other bereaved families in their work for justice in the UK.

The event will feature contributions from Clarke’s sister Tellecia Strachan, and Marcia Rigg, campaigner and sister of Sean Rigg, who also died in similar circumstances in 2008.

Anthony Grainger

The IOPC dropped the second of three investigations into three ex-Greater Manchester Police officers over the fatal shooting of Anthony Grainger because ‘some of the material which may be relevant to the decisions to be made at the conclusion of any investigation, and to provide adequate disclosure to the officers, could not be disclosed’ (Manchester Evening News, 03 Feb).

The officer who fired the shot [Q9] had already avoided disciplinary action, due to the IOPC ruling that the officer had acted ‘honestly’, despite a public inquiry into the shooting in 2019 revealing Q9 had been presented with seriously inaccurate intelligence, which exaggerated the risk posed by Mr Grainger.

The IOPC’s statement said: ‘The third of our investigations into GMP's acquisition of a CS dispersal canister which was not approved by the Home Office and was used during the policing operation in which Mr Grainger died continues.’

Brian Ringrose

Five Thames Valley officers have been advised they are under criminal investigation following the death in police custody of Brian Ringrose in Milton Keynes earlier this month (Independent, 24 Feb).

The IOPC report states that after suspending arrest for an ambulance to transport him to Milton Keynes University Hospital for treatment, officers restrained Ringrose using a Flexible Lift and Carry System (FLACS) as soon as he was medically discharged. However, Ringrose was soon returned hospital where he was placed in an induced coma, and later died in hospital.

Thames Valley has suspended its use of FLACS equipment while the investigation is carried out.

Moyied Bashir

A second person of colour in Wales has died following police contact since the start of the year.

Moyied Bashir’s family reported that he was having a mental health crisis, but when they called Gwent Police for help, 24 officers arrived, ‘forced’ their way into his room, handcuffed and applied leg restraints on him, before being taken to hospital, where he later died (BBC News Wales, 19 Feb).

Gwent Police have referred themselves to the IOPC over the matter.

BLM to fund a ‘people’s tribunal’ for deaths from police custody

Black Lives Matter UK has announced £45,000 of funding to the United Families & Friends Campaign (UFFC) to set up a ‘people’s tribunal’ for deaths in custody (Guardian, 17 Feb). UFFC is leading the initiative with Migrant Media and 4WardEverUK.

According to a letter from the UFFC, they aim to establish in the UK context: the failure of State officials to ensure the basic right to life is made worse by the failure of the State to successfully prosecute those responsible for custody deaths; and the failure to successfully prosecute those responsible for deaths in custody sends a message that the State can act with impunity.

Evidence regarding the above from families and other relevant parties will be presented to an international panel in a public forum. The panel’s decisions will then be implemented with the support of international bodies.

Section 60 watch*

London

Barking & Dagenham (21 Feb), Brent (19 Feb), Islington (01 Feb), Croydon (06 Feb), Hammersmith and Fulham (11 Feb), Wandsworth (06 Feb), Westminster (06 Feb)

Thames Valley

Langley, Slough (09 Feb), Reading (14, 22 Feb)

* This is not a comprehensive list

Terrible tech – film everything

If we are going to live in a surveillance state where everyone is recorded all of the time, some may think it would be remiss of them not to join in the filming. When mobile phone footage is the only thing that saves you from being deemed guilty in a magistrates’ court because of the lies of police officers, it’s hard to argue against the point (BBC News Cornwall, 08 Feb). There is also something to be said for automatically dismissing all prosecutions where body worn video of police-civilian interactions is not produced at the court’s behest.

It is odd that the police should be so opaque about their use of tech though. They normally love showing off new gadgets, like drones, for instance. Now organisations such as UK Drone Watch have to use freedom of information requests to find out about forces’ use of drones at protests (12 Feb).

Furthermore, polling indicates strong concerns among the public over drone use: of 2,000 people questioned, 60% were worried about the effects on privacy and civil liberties, and 67% said they were concerned about the safety implications.

Still, perhaps there is a desire to want to deal with the sensitive issue of data use responsibly. The Met Police is looking to hire a Data Ethics Lead to make sure that their rank-and-file ‘understands the ethical boundaries that come with data use’.

That can only be a good thing, right? Big Brother Watch director Silkie Carlo thinks otherwise, and with good reason – why pay someone to analyse police data in-house that many campaign groups and experts already do for free?

Two sides of mayor Khan

February started so well for Mayor of London Sadiq Khan: his review into the police’s gangs matrix database led to the removal of 1,000 young Black men’s names, after 38% on the list were found to pose ‘little or no risk’ (Guardian, 03 Feb).

So far, so good. But then reports suggested Khan was considering adding police officers to some London schools post-lockdown ‘to help prevent a surge in violent crime’ (BBC News London, 16 Feb). Khan’s call came a few days after Mayor of Greater Manchester Andy Burnham committed to placing officers in schools (Manchester Evening News, 11 Feb).

This prompted a less-than-enthusiastic reception from criminal justice and child safety campaigners. Roxy Legane, founder of Kids of Colour, called out the fact that a greater police presence anywhere tends to result in ‘the further encroachment of institutional racism and oppression into people’s everyday lives’, and called for the adoption of ‘alternatives we know will set the foundations for positive childhoods and futures’, such as ‘more funding for schools themselves and for the youth workers, counsellors, sex educators, behavioural experts and so forth that should sit within them’ (Ceasefire Magazine, 21 Feb).

A Freedom of Information request from VICE last year revealed that the number of police officers (known as Safer Schools Officers, or SSOs) at London schools rose 20% in the four years to 2019/20, with the Met Police planning to add more in the following years. But is there any evidence to justify the expansion of officers?

Evidence seems to be sorely lacking if we take the Met’s pledge last year to review its Safer Schools Programme after the family of a 14-year-old autistic black pupil, who was investigated by the Crown Prosecution Service following a verbal disagreement at his school, began judicial review proceedings. Or if we raise the case of a London-based parent, backed by Just For Kids Law, whose daughter was put through a two-year ordeal to clear her name of the charge of carrying a ‘bladed item’ to school – ‘the item in question being a small pair of hair-cutting scissors’, Legane writes.

And what evidence is there of parents electing to have officers patrol their schools? On the contrary, The Justice Gap reported that a joint report from No Police in Schools, Kids of Colour and the Northern Police Monitoring Project in November 2020 revealed concerns that ‘a police presence would stigmatise schools’, with ‘almost three quarters of parents and guardians (72%) saying they would have concerns about sending their child to a school with a SBPO [school based police officer]’.

With roughly 10 million residents to serve, it is understandable that the mayor Khan, as the capital’s crime commissioner, has a difficult task balancing the many interests and views of his constituents while keeping them safe. However, Khan would be better off if he implemented safety initiatives from an evidence and community consent based standing rather than a rhetoric-based one.

In other news

Criminalising a way of life: Solicitor Cormac Mannion warns of the potentially damaging effects of the proposed Police Powers and Protection Bill on the livelihoods and rights of the UK’s Gypsy, Roma and Traveller (GRT) communities by criminalising trespass and unauthorised encampments (Hodge Jones & Allen, 09 Feb).

Rogue cops: A radio documentary on the behaviour of so-called ‘rogue cops’ asks ‘what the science of criminology has discovered about how such tragedies can be stopped?’ (BBC Radio 4 Analysis, 08 Feb).

Can’t reform them: The Voice newspaper interviews academic and author of Black Resistance to British Policing Dr Adam Elliot-Cooper about why he thinks popular police reform ideas are not what our community needs, and why we should defund them instead (22 Feb).

In Memoriam: Judge Sir William Alan Macpherson of Cluny, 6th of Blairgowrie (01 April 1926 – 14 February 2021)

We pay tribute to Sir William Macpherson, the British high court judge who died this month aged 74 years. He is noted for leading the public inquiry into the murder of Stephen Lawrence, and his 1999 report into the tragedy and its circumstances was one of the most significant moments in the history of UK criminal justice.

Sadly Sir Macpherson did not live to see all of his much-needed recommendations into the reform of the police implemented, but he was pleased to have achieved what he did. The Scotsman reported that in a 2019 interview he said: ‘There's obviously more to be done, but my feeling is that great steps have been taken in the right direction.’

Now it is up to us to take the mantle on and make further progress.

StopWatch is a volunteer led organisation that relies on the generosity of trusts and grant funders to operate. We DO NOT accept funding from the government or police as we believe this would compromise our ability to critically challenge.

We appreciate regular donations via standing order, if you’d like to pledge your long-term support. Details are:

CAF Bank – Registered office: CAF Bank Ltd, 25 Kings Hill Avenue, Kings Hill, West Malling, Kent, ME19 4JQ

Account Name: StopWatch | Sort Code: 40-52-40 | Account Number: 00027415

—

Stay safe,

StopWatch.