February 2022: Dick out

Met police chief resigns after report reveals casual and violent language used by officers based at a central London police station

Dear StopWatchers,

The shortest month brings the longest amount of intrigue and speculation over the state of British policing, as the head of the biggest force steps down in controversial circumstances. Predictably, some (namely deputy commissioner Sir Stephen House and the Police Federation) rallied around their fallen commander ways that give the impression the police care more about the way Dame Cressida Dick departed than the extent to which the reprimanded officers – several of whom kept their jobs thanks to a sanctions system that would please a Russian oligarch – hate particular elements of the public they allegedly served. They seem less concerned about the impact of their officers’ attitudes towards women, ethnic minorities, gay people, and Muslims on the way they interact with Londoners on the streets, and the inevitable pain and hurt they would have caused.

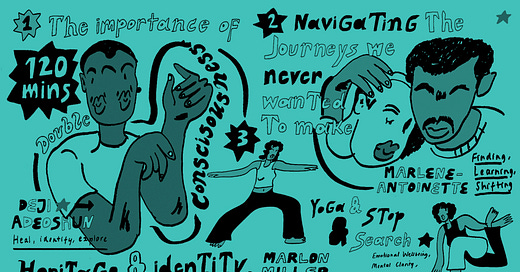

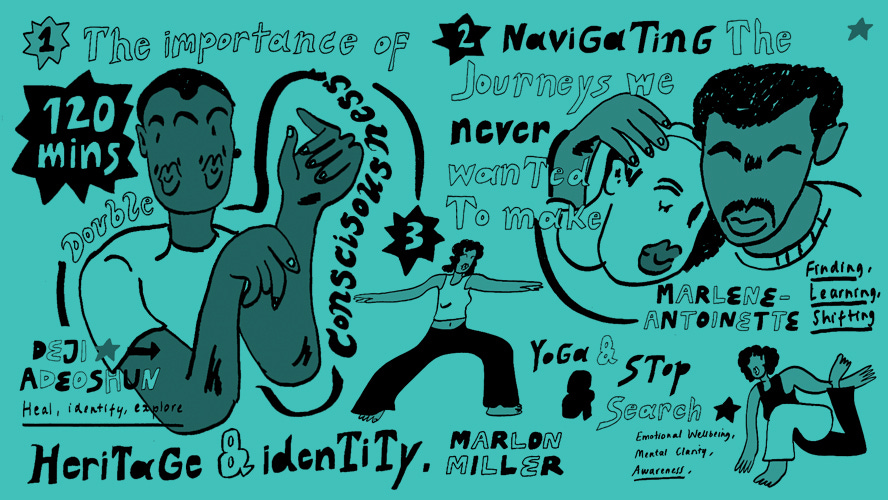

Where they ignore this, we aim to address it by providing not just legal, but therapeutic support for those who suffer from instances of injustice meted out by police officers. From March, we are launching a series of free sessions under our pioneering Rights And Wellbeing (RAW) project which aims to help impacted communities address the trauma arising from stop and search encounters. Click through to our EventBrite page to find out more.

Topics in this newsletter include:

London’s police chief to quit post early after mayor withdraws support in wake of Operation Hotton scandal

Liberty take Met to court over gangs matrix

Bristol Copwatch founder launches case against Avon & Somerset Police for a serious data breach

And in Terrible tech, parliamentary peers express regret over a surveillance camera code of practice while facial recognition ready police equipment sprouts across the country

Please enjoy our roundup of stories below.

Dick out

Barely a day after the last newsletter dropped, another story of epic police misconduct surfaced in the press, making January seem a very distant memory. February began with Operation Hotton: revelations of misogynistic and racist communications between officers stationed at the epicentre of the country’s most cosmopolitan city (Guardian, 01 Feb).

A spokesperson for the Metropolitan police remarked that in an organisation of more than 44,000 people, there will be a small number with attitudes and beliefs, but that the force will ‘challenge, educate and discipline as appropriate’. In the end, it was ‘appropriate’ for 9 of the officers to stay in the force, and for 2 to gain promotion (Guardian, 02 Feb).

This enraged the capital’s mayor, who demanded commissioner Dame Cressida Dick come up with a plan of action to deal with the most egregious elements of police culture, sharpish. However, whatever was produced was so lacking that Sadiq Khan felt he could no longer maintain his faith in her leadership, and so Dick felt she had no option but to step down (BBC News, 11 Feb), even after assuring listeners only hours earlier on BBC Radio London (10 Feb) that she was going nowhere, all of which added an element of farce to proceedings.

It was only in September of last year that Khan approved a 2-year extension of her contract. However, the noise surrounding a long run of bad results and plummeting public confidence made for the Dame’s downfall in the mayor’s eyes, whose patience wore thinner than that of your average football club supporter. To put it another way, in only 4 months he went from ‘In Dick We Trust’ to ‘Dick is no longer at the wheel’.

So much rot you could make cider from it

Typically, we’ve witnessed much debate over her tenure and speculation over who might succeed her. But if you believe the problems with police culture and procedure are systemic, then assessing Dick’s merits as a commissioner is irrelevant. Take the aforementioned Charing Cross police station scandal; the messages revealed date back to before the Dame became commissioner (2016–2018).

When you have a police culture that exhibits institutional racism (stop and search), misogyny (domestic violence / sexual assault cases / spycops), homophobia (Stephen Port) and corruption (Daniel Morgan) dating back decades at least, then it is clear that the force’s problems are greater than just the head.

Those who know this are unsurprised by the news that the number of police officers throughout all of England and Wales sacked without notice for gross misconduct over a recent 3-year period (BBC News, 11 Feb) is roughly the same as the number of civilians who die following contact with the police or in their custody every year.

Or that it would take for a tragic event such as Sarah Everard’s murder to catalyse a sharp upswing in the recording of many more sexual assaults by officers that normally go unreported for fear of reprisals or lack of faith in the justice system (Telegraph, 19 Feb, £wall).

But is it in a police chief’s power to change the culture at all? From the outside (and even to some of her own officers), Dick’s words and (in)actions implied that she did not believe she needed to, as former head of the Metropolitan Black Police Association Janet Hills MBE told the Times (14 Feb, £wall):

On the Charing Cross revelations, she said: ‘In terms of the problems in existence when I left, the fact that this bubbled up is of no surprise to me because that is just one of many.

‘The hope was, given the commissioner’s protected characteristics, that she would come with something fresh and new but we’ve just not seen it.’

In her dealings with Dick on racism in the force, she said that ‘there was a realisation that the problem existed but it felt like for her whenever we had the conversation that that was something in the past.’

She said: ‘It felt like “that was then, this is now”, but we hadn’t changed enough and that was the reality of it. The lived experience of officers from an African and Caribbean background wasn’t on a par with their white colleagues.’

Of course, it is hard to change the culture and root out rogue officers in the process. Only last year did College of Policing head Andy Marsh expressed his frustrations with the fact that as many as 1 in 4 misconduct hearings are still held in private.

But even a slight admission of the rotten state of things at the Met was too much for Dick, who only acknowledged as much after announcing her departure.

If Londoners (and the rest of the country), are to have a force that works for them, they’ll need someone who is going to try a little harder to improve policing standards than their predecessor. Sadiq Khan has made that a bare minimum requirement for whoever the next commissioner may be (CityAM, 13 Feb). Whoever it is, we wish them the best of luck cleaning that crop. No, seriously, we do.

And we look forward to liaising regularly with them, as we did with Dick, apparently.

Deaths from police contact, cases old and new

Unknown

A man who has died in police custody at Kirkcaldy police station is the third person to do so in 7 years (The National, 23 Feb).

The deceased’s next of kin has been informed and the police investigations and review commissioner is undertaking a Crown directed investigation into the circumstances surrounding his death, which occurred on the same day of a preliminary hearing into the death of Sheku Bayoh, who died at the same station in 2015.

Other news*

Met Police face court battle over gangs matrix: Liberty is taking legal action on behalf of 2 clients (Awate Suleiman and UNJUST) against the Metropolitan police to challenge the gangs matrix – a secretive database of suspected gang members established as part of the response to the 2011 London riots (The Independent, 02 Feb).

Pointing out that the matrix is ‘fuelled heavily by racist stereotypes which aren’t borne out in reality’, a spokesperson told the paper that ‘it is an undeniable fact that the gangs matrix is not evidence based, and Black people are overrepresented on the matrix, both compared to the general population and to the rates of conviction for relevant offences’.

Rastafarian woman humiliated by police strip order: The case of a Rastafarian woman who was sat naked in a police cell shows officers need greater understanding of minority groups, ex-senior officers have said (BBC News, 02 Feb).

Yvonne Farrell said she was humiliated after being made to sit naked in a cell for 3 hours following her arrest by Hertfordshire Police.

Police officer warned for using CS spray on a child: A Greater Manchester Police (GMP) officer received a written warning for his use of CS spray during the arrest of a 13-year-old, following an investigation by the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC, 03 Feb).

IOPC regional director Amanda Rowe said: ‘We found no evidence the boy posed any immediate threat to police or the public and the officer’s conduct during the incident fell short of what would be expected of a serving officer’.

Met strip-searches are racially disproportionate: A freedom of information request on the Metropolitan Police’s use of strip-searches has revealed that Black people remain over represented in the force’s use of the humiliating and degrading practice (The Canary, 17 Feb).

Met police carried out a staggering 172,093 strip searches in the past 5 years.

In spite of calls to reduce the force’s use of the humiliating and traumatic practice, Dr Tom Kemp (who carried out the research) noted a peak of around 34,000 strip-searches in 2020 which ‘continued a trend in increasing use of strip searches from before the pandemic’. Kemp’s analysis also revealed that 33.5% of strip-searches (57,733) carried out by the Met police in the last 5 years were on Black people, who represent around 11% of London’s population.

Copwatch challenges data protection breach: Founder of police monitoring group Bristol Copwatch John Pegram is launching a case against Avon & Somerset police on the grounds that the force is in breach of data protection laws after wrongly entering his data on the Police National Computer after an encounter at a protest in 2018 (The Canary, 13 Feb). As Pegram, a mixed-race Black man, sets out in his CrowdJustice appeal:

The information on my PNC record is real time information provided to officers on the street. It’s the sort of information that is shared in intelligence briefings and could influence senior officers decision making. We need only look at how willingly the police use force against Black people to understand the implications.

Changes to out of court disposals in PCSC Bill raise concern: Aileen Colhoun, partner in Hickman & Rose’s Serious and General Crime department, analyses a hitherto little-noticed aspect of the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill: the impact on adult out of court disposals (12 Feb).

Home sec lobbies MPs to back PCSC Bill plans: Home secretary Priti Patel wrote to all MPs urging them to back her plans to overturn the defeats inflicted by Lords over amendments to the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill as it returns to the lower house (The Independent, 21 Feb).

Plans include looking to reintroduce increased police powers for dealing with ‘highly disruptive protests’, a policy that has sparked #KilltheBill demonstrations across the country.

* Please view the Institute of Race Relations calendar of racism and resistance for a comprehensive list of policing articles.

Section 60 watch*

London

Ealing (17 Feb), Hounslow (17, 18 Feb)

Thames Valley

Milton Keynes (11, 12, 14, 15, 21 Feb), Oxford (25 Feb)

West Midlands

Dudley (04 Feb), Birmingham (16, 17 Feb)

Manchester

Leigh, Atherton & Hindley (02 Feb), Greater Manchester (06 Feb)

South Wales

Rhondda (03 Feb), Cardiff (11 Feb)

* This is not a comprehensive list

Terrible tech: Burning Bridges

Last month, parliament approved the updating of the surveillance camera code (Home Office, 12 Jan). A few weeks later, Lord Clement-Jones brought the following motion to his fellow peers (Hansard, 02 Feb):

That this House regrets the surveillance camera code of practice because (1) it does not constitute a legitimate legal or ethical framework for the police’s use of facial recognition technology, and (2) it is incompatible with human rights requirements surrounding such technology.

A Motion to Regret carries no bearing on the legislation passed, unfortunately; the code is here to stay for now. But it is at least useful in pointing out problems that could be addressed at a later stage by better policy.

And there were many. Lord Clement-Jones’s opening statement outlined his regret that the new code fails to address the concerns raised by the trial verdict from R (Bridges) v the chief constable of South Wales police:

The previous surveillance code of practice failed to provide such a basis. This, the updated version, still fails to meet the necessary standards, as the code allows wide discretion to individual police forces to develop their own policies in respect of facial recognition deployments, including the categories of people included on a watch-list and the criteria used to determine when to deploy… This scant guidance cannot be considered a suitable regulatory framework for the use of facial recognition.

His observation is all the more alarming given that the police have form for mishandling information on databases (see ‘gangs matrix’) and as Lord Rosser noted, ‘a High Court ruling in 2012 saying that the police were unlawfully processing facial images of innocent people’. It is clear that normalising facial recognition deployments further serves to minimise the seriousness of this issue.

Clement-Jones also lamented the invasive nature of the technology in the context of ‘false matches’, but again, there are precedents that police forces can now use in their defence. Every day, countless drivers are stopped in their cars purely on the whim of police officers abusing automatic number plate recognition (ANPR) technology. With the advent of live / automated facial recognition (LFR / AFR), what applies to vehicles on the roads can now apply to people on the pavement.

The peer also noted how ‘[t]he disproportionate use of this technology in communities against which it “underperforms” — according to its proponent’s standards — is deeply concerning.’ These ‘communities’ often involve people (especially women) of colour. We share Clement-Jones’s fear that – contrary to one of the specifications of the Bridges v South Wales police court ruling – forces will ignore the public sector equality duty (PSED) when using the technology because the code does.

Worse still, PSED watchdog the Equality and Human Rights Commission was not even consulted on discussions over the ensuring the code complies with the Bridges judgment, a situation which chair Baroness Falkner of Margravine noted her ‘deep regret’ over. She is uncertain whether it does.

The Home Office’s representative in the Lords (Baroness Williams of Trafford) failed to ease worries when Lord Rosser asked what ‘equality impact assessments’ of the tech’s application in respect of the PSED will look like in practice, opting instead to praise the accuracy of the technology, making at least 3 claims free of the context needed to take them at face value:

‘LFR trials have resulted in 70 arrests’ [out of how many stops?]

‘At a Cardiff concert there were no reported mobile phone thefts when South Wales police used LFR, where similar concerts in other parts of the UK resulted in more than 220 thefts’ [not a like-for-like comparison]

‘South Wales police and the Met have found no evidence of bias in their algorithms and, as I said, a human operator always takes that final decision’ [so after all the hyped improvements promised by the new tech, the public will still rely on the judgment of a representative of an institutionally racist, misogynist, homophobic (and in some areas) corrupt police force? Well that’s alright then, as you were].

Besides, the harvesting of so much footage raises another problem: all too often, police work in concert with private actors (usually businesses) to surveil sites of public commerce, as Clement-Jones observed:

… the Trafford Centre in Manchester scanned the faces of every visitor for a six-month period in 2018, using watch-lists provided by Greater Manchester police—approximately 15 million people. LFR was also used at the privately owned but publicly accessible site around King’s Cross station. Both the Met and British Transport Police had provided images for their use, despite originally denying doing so.

Lord Anderson remarked that image databases ‘are not all owned by the police: the company Clearview AI has taken more than 10 billion facial images from public-only web sources and boasts on its website that its database is available to US law enforcement on a commercial basis.’

So what safeguards does the code have in place to protect us from police-induced data breaches? Baroness Williams told the chamber to hold tight for the College of Policing’s national guidance.

Meanwhile, any force that deploys facial recognition risks coming across another Ed Bridges. This is why Lord Clement-Jones said that it ‘does not really seem satisfactory’ for the government to ‘wait around until the next round of judicial review and the next case against the police demonstrate that the current framework is not adequate’.

Lights, camera, data protection

Many police forces have pressed ahead with purchasing LFR-friendly equipment. Data obtained by civil liberties campaigners Big Brother Watch through freedom of information requests found 15 are using Hikvision and Dahua cameras, which have advanced surveillance capabilities including facial, gender and behaviour detection (Times, 07 Feb, £wall).

And when you add the desire of forces to test out ever more advanced equipment (Norfolk police to pilot drones with 20 mile range (Eastern Daily Press, 07 Feb)), all-too frequent instances of data misuse (a recent audit of Greater Manchester police concluded that there is a ‘limited’ level of assurance that processes and procedures are in place for are delivering data protection compliance (ICO, 01 Feb)), plus lawmakers’ intentions to make data protection laws more ‘business-friendly’ (The Telegraph, 22 Feb, £wall), those of us who fear the tech will be used to surveil marginalised, overpoliced communities (despite the College of Policing’s national guidance) must now expect it. After all, it is already happening elsewhere (Techdirt, 11 Feb).

StopWatch is a volunteer led organisation that relies on the generosity of trusts and grant funders to operate. We DO NOT accept funding from the government or police as we believe this would compromise our ability to critically challenge.

We’d appreciate any one-off or regular donations to help support our work. You can click on our Donate button below to go through to our donation page.

—

Stay safe,

StopWatch.