July 2020: The police – drivers of disproportionality

As evidence of racist policing continues to pile up, the IOPC gives the green light to conduct yet another review

Dear StopWatchers,

Another month brings another set of policing controversies, to which this newsletter cannot do full justice, as many and as varied as they are. But sometimes many stories can centre around a common theme: on this occasion, car stops.

The lack of information recorded by the police on vehicle stops is a serious blind spot that needs addressing if we wish to achieve fair and accountable policing. However, despite the fact that this (and more) was recommended in an inquiry more than 20 years ago, the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) would prefer to conduct another review into police racism. We are wary of reviews becoming a bottleneck for real action, as our Chief Executive Katrina Ffrench tells Business Insider in a video about recent protests led by the Black Lives Matter movement.

Still, StopWatch will continue to fight and raise awareness of police injustice, and you can join us and fellow campaigners to protest against police racism, violence, and impunity. When? Saturday 08 August, 1PM. Where? Tottenham Police Station.

Topics in this newsletter include:

An update on UK policing during the coronavirus pandemic

The problem of Driving While Black, and other examples of policing prejudice

The racist culture of policing within the force itself

A focus on TASER® use

Pressure to scrap Section 60 grows – demonstrations are held against the practice

Manchester cinema hosts online screening of documentary on Joint Enterprise

A call for non-lethal restraint

Please enjoy our roundup of stories below.

Coronavirus update

In the latest instalment of the Coronavirus Chronicles: Community Policing edition, the UK Government refuse to repeal their own legislation, which has been shown so far to be totally unnecessary (The Independent, 16 Jul). And by ‘totally’, we mean 💯:

All 89 charges brought [and finalised in England and Wales by the end of June] under the Coronavirus Act 2020 have been overturned… Another 26 charges under the separate Health Protection Regulations, which enforce lockdown restrictions, were found to be unlawful by the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS).

Police data analysed by National Police Chiefs’ Council also showed that twice as many fines were issued to young male adults under the age of 35 from BAME backgrounds compared with young white men of the same age (Metro UK, 27 Jul).

Still, there’s always plain ol’ stop and search to fall back on: analysis of Metropolitan Police data confirmed that the force carried out 22,000 searches in the capital between March and May, with four out of every five resulting in no further action taken (The Guardian, 08 Jul). And with the introduction of Violence Suppression Units to the capital (Sky News, 25 Jul), there are no signs of the tensions between police and the communities they operate in cooling down any time soon.

For those Londoners reading this, imagine 80% of your force’s searches producing nothing of use. Think of all that wasted energy on the part of your officers. Then put yourself in the shoes of a commanding officer. Would you not be alarmed?

Well, never fear, because Met chief Cressida Dick isn’t, hence this exchange with Home Affairs Select Committee Chair Yvette Cooper over May’s figures during a parliamentary session (video):

Cooper said data showed 10,000 Black males in London aged 15 to 25 were stopped and searched in May. Total population estimates for that demographic in London are between 70,000 and 80,000.

Cooper said: “That suggests in one month alone, more than one in 10 of young Black men in London were stopped and searched and found to be carrying nothing and found not to be doing anything that required further action. That’s just in one month also at a time when actually most people would have been at home during lockdown.”

Asked if the figures alarmed her, Dick replied: “I’m not alarmed, I’m alert.”

Perhaps the commissioner might be alarmed at the fact that the police have potentially failed to adhere to their own coronavirus law guidelines on a routine basis? The deployment of personal protective equipment (PPE) is rare by all accounts, and so tens of thousands of people searched have potentially been put at risk of contracting COVID-19, as Honorary Academic and Research Fellow at the University of Liverpool Ghaith Aljayyoussi notes (The Conversation, 09 Jul):

Guidance to the police focuses on the use of PPE for the protection of police officers and emphasises that “officer safety is paramount in responding to situations” while ignoring public safety. The guidance discusses “the possibility that infected occupants do not know that they are infected”. The possibility that the officers themselves not knowing they are infected is ignored.

As long as the Coronavirus Act exists on the nation’s statute books, the police must be held accountable for enforcing it, and when they fail in that duty, trust in them erodes. Northern Ireland is proving a prime example of what happens when a section of society takes issue with the manner in which they are policed (The Irish News, 25 Jul).

Ethnic minority community leaders are refusing to engage with Chief Constable Simon Byrne until he makes a public apology and the “PSNI drop all fines and threat of legal action” over socially distanced anti-racism protests.

Up to 70 people were penalised for breaches of coronavirus lockdown regulations after enforcement powers were given to the PSNI at 11pm on Friday 5 June.

There was an outcry a week later after no fines were issued when hundreds of people gathered to “protect Belfast cenotaph” outside City Hall – with many participants reportedly not social distancing.

The police – drivers of disproportionality

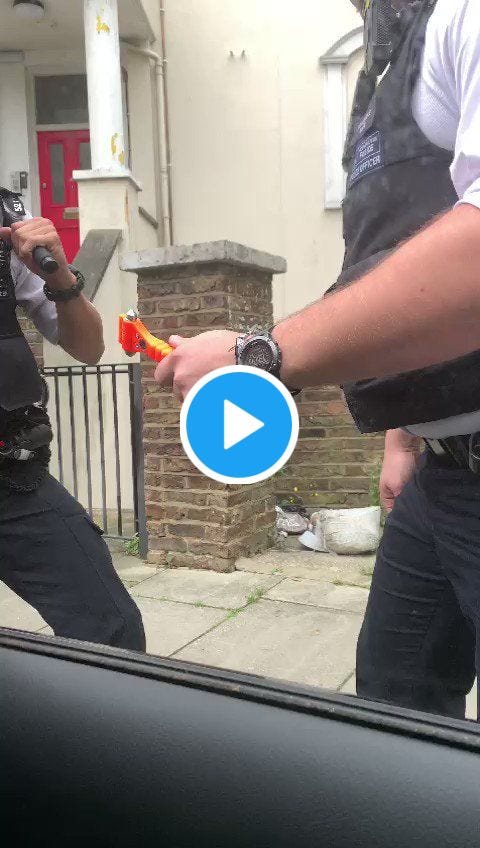

During the session to the Home Affairs Select Committee, commissioner Dick also apologised to athlete Bianca Williams ‘for the distress that her stop clearly caused her’ in the highest profile case of racial profiling this month. The police stopped her partner, Ricardo dos Santos (also an athlete) as he was driving the couple and their baby in Maida Vale, London (BBC News, 04 Jul). Video footage of the incident was posted on social media by former Olympic sprint champion Linford Christie.

Another incident involved Bradford City footballer Ben Richards-Everton, confronted by officers in his vehicle in Sutton Coldfield, near Birmingham (BBC News, 14 Jul).

What attracts police to make so many stops? A report we co-wrote with Liberty in November 2017 – Driving While Black – suggests that when it comes to racial disparity, there is a blind spot in roads policing: as it stands, Section 163 of the Road Traffic Act gives police broad powers to stop anyone they wish driving on the roads without suspicion, but does not require them to record the number of traffic stops, who is being stopped or the outcome of these stops.

The effect of this is the sort of policing that contributes to the long held fear among ethnic minorities that vehicle stops are a ruse for racial profiling, a view bolstered by evidence produced from text analysis of language used by police officers during stops, which find that officers speak with ‘consistently less respect’ toward Black versus White drivers, ‘even after controlling for the race of the officer, the severity of the infraction, the location of the stop, and the outcome of the stop’.

Somehow, vehicle stops fall outside the scope of stop and search fair policing guidance, and are not subject to basic safeguards such as recording and monitoring, a discrepancy that dates at least as far back as the recommendation for the police to record driver ethnicity for vehicle stops, as per the Macpherson inquiry:

However, we’ve made no headway on implementing this rule, over 20 years later. Why? What are the police afraid of?

An endless journey of prejudice

Ultimately, vehicle stops are but one of many sources of racial disparity in stop and searches, for whether driving or on foot, the facts show that such disproportionality is returning to levels outstripping those seen in the run-up to the 2011 riots.

An in depth study from the New Statesman on the issue (17 Jul) mines through the data to depict what is for many an ‘endless journey of prejudice in the police and justice system’:

And a special investigation of a small selection of households in Brixton, south London, found huge discrepancies in the way they had been treated by the police ‘purely on the basis of colour and ethnicity’ (London Evening Standard, 26 Jul).

Will anything be done about it though? Well, as is customary when the British state is forced to address substantial grievances from a portion of the public, it rises to the challenge with an inquiry: the IOPC will launch a review into police ‘race discrimination’ (BBC News, 10 Jul). We might yet discover something we didn’t already know, but we won’t hold our breath.

Police racism within the force

Ex-members (The Guardian, 22 Jul), and serving personnel (BBC News, 19 Jul) have been speaking out about the racism they’ve suffered within the profession in recent months.

But former Black police officer for Merseyside Constabulary Chañtelle Lunt asks why we have not been talking about it all this time? Writing in Rattle Liverpool magazine (09 Jul), Lunt draws on her painful experiences as a member to describe how the culture breeds the sort of public servant whose interests do not match those whom they serve.

Terrible tech: On TASERS®

The police investigation into to the case of unarmed 62-year-old Millard Scott, who was sparked by officers on his own doorstep in north London, concluded that no further action will be taken (BBC News, 16 Jul).

After bouncing the case between themselves, the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) then passed it back to the Met, who declared that they would close the case as there had been ‘no public complaint or indication of misconduct’, although the IOPC said it had in fact decided not to investigate after Scott’s family refused to cooperate with them.

So Scott’s family are considering suing the force instead. Millard’s brother, Stafford Scott of The Monitoring Group, told The Guardian (16 Jul) that his family would never go to the IOPC because ‘we don’t believe they are independent or competent or able to hold the police to account’.

The furore over this TASER® incident is simply one example of what the Institute of Race Relations (IRR) have dubbed ‘an increasingly British phenomenon’:

Some people think that to tackle criminality, you have to get to the source of it, or the Origins, if you’re former Equality and Human Rights Commission chair Trevor Phillips. His consultancy, run with professor Richard Webber, has engineered software for the purpose of identifying whether different ethnic groups ‘specialise’ in particular types of crime (The Guardian, 27 Jul), and as ever, being the early adopters they are, the Met Police have started to use it. Not for the purpose intended though, they claim, but instead ‘to enable safer neighbourhood teams to better understand the communities they serve’, whatever that means.

However, this kind of predictive policing tech is often the refuge of police forces too contemptuous or afraid to do the hard work of liaison and persuasion, and so its use serves to turn the delicate art of community policing into an arms’ length operation.

Commenting on Origins, a spokesperson for the IRR said:

Police use of this software heightens already well-aired concerns about racial profiling. The fact that the Met and other police forces now see a need to rely on such data analytics in order to reach an ‘understanding of the communities’ within their areas is a sign of just how far we have moved away from the traditions of community policing and policing by consent, due in no small measure to their disproportionate and excessive use of stop and search, handcuffing and Tasers against Black people.

A group of academics (including Cathy O'Neil, author of a book on the issue of algorithms in policing, Weapons of Math Destruction) understand this. According to a letter submitted to the journal Notices of the American Mathematical Society, they appealed to fellow researchers to stop all work related to predictive policing software (Popular Mechanics, 20 Jul):

“Given the structural racism and brutality in U.S. policing, we do not believe that mathematicians should be collaborating with police departments in this manner,” the authors write in the letter. “It is simply too easy to create a ‘scientific’ veneer for racism. Please join us in committing to not collaborating with police. It is, at this moment, the very least we can do as a community.”

Section 60 watch*

London

Brent (18 Jul), Ealing (09 Jul), Hammersmith & Fulham (03 Jul), Hillingdon (09 Jul), Hounslow (09 Jul), Merton (20 Jul), Southwark (23 Jul), Tower Hamlets (20 Jul)

Essex

Barking & Dagenham (20 Jul)

Merseyside

Kirkby (13 Jul)

Wales

Shotton, North Flintshire (13 Jul)

* This is not a comprehensive list

This month has seen ‘Scrap Section 60’ demonstrations held in Stoke Newington and Brixton, the latter attended by MP for Streatham Bell Ribeiro-Addy and former police superintendent Leroy Logan MBE, who made the case in a Sky News interview (25 Jul).

There is also a Scrap Section 60 petition available for those interested in pledging their support to the campaign. And with good reason, as data collected by the human rights group Liberty through freedom of information requests reveals that in May, the Met Police stopped and searched (without suspicion) more than double the number during the same month last year under the power.

As for the number of Section 60 orders given that month, they issued 65 such authorisations in May, a sharp rise from 13 times in April and higher than equivalent months in recent years (The Guardian, 27 Jul).

The spike in volume of searches comes despite data from the National Police Chiefs’ Council showing that crime levels were falling before the coronavirus lockdown came into force. Liberty’s findings suggest that subsequent enforcement of the lockdown ‘have followed patterns of discrimination’ usually shown in stop and search.

Dangerous Associations, a short film on Joint Enterprise

This month saw HOME MCR cinema host the online screening of Dangerous Associations, a documentary created by local filmmaker Colin Stone about the use of Joint Enterprise within our criminal justice system. Drawing on research from Manchester Metropolitan University, the film examines why so many convicted under this common law are young Black men.

A call for non-lethal restraint

For those who say George Floyd style tactics ‘don’t happen here’, the choking by the knee of a man's neck by police in Islington earlier this month (BBC News, 17 Jul) is too disturbing a parallel to deny, even for Deputy Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Steve House, although he was quick confirm that some of the techniques the officers used in restraining their target ‘are not taught’ in police training.

Not taught, perhaps, but still used. The Met’s own Use of Force dataset found that officers in the capital used force 159,000 times in 2019-20, with more than a third of cases involving Black people (BBC News, 30 Jul), Restraint rates were 18 times per 1,000 of the population on average for them, compared with five times per 1,000 for whites. What is most telling, however, is the attitude behind the data. A serving officer, who spoke to the BBC on condition of anonymity, said:

As far as they're concerned black people are more aggressive.

You should calm them down but instead they are keen to put hands on first because it's flight or fight.

Particularly with black men, if a black person is upset, saying “it's hurting”, they say “it looks fine to me”.

Excessively violent restraint is not unique to US forces, as the families of Rashan Charles and Sean Rigg know. Sean’s sister Marcia told The Telegraph (08 Jul) the footage of George Floyd made her ‘mad as hell’ and that now is an ‘appropriate’ time to push for a change of the law. She said:

Absolutely nothing has changed because so many people have died since Sean's death.

Officers... can restrain somebody for up to a period of seven minutes and that is deemed to be not excessive by the Metropolitan Police. How can that be?

Ultimately, there can be no excuse for using restraint techniques that the officers involved must have known would be problematic. Stop and searches would benefit greatly from police officers exercising non-lethal forms of restraint.

Thank you to all those who donated to our summer fundraiser! We’ve raised a huge amount so far. With your help we can still reach our hallowed £125,000 target, which gives our pursuit of proper justice for victims of unfair policing a huge boost. Please feel free to share our GoFundMe page with anyone you feel might be interested making in a one-off donation to our cause.

We’d also appreciate regular donations via standing order, if you’d like to pledge your long-term support. Details are:

CAF Bank – Registered office: CAF Bank Ltd, 25 Kings Hill Avenue, Kings Hill, West Malling, Kent, ME19 4JQ

Account Name: StopWatch | Sort Code: 40-52-40 | Account Number: 00027415

—

Stay safe (and alert, but not alarmed),

StopWatch.