June 2023: Suella's stop and search scheming

This month, the home sec called for the 'ramping up' of stop and search to tackle 'knife crime'. It won't work – but she doesn't care

Dear StopWatchers,

As usual, it’s not been a great month for UK policing; consequently, we’ve been busy here at StopWatch. An investigation by the BBC into the racist murder of Stephen Lawrence in 1993 uncovered more serious failings in the Met’s handling of the case, and prompted the force to take ‘the almost unprecedented step’ of publicly naming Matthew White (who died in 2021) as a suspect (BBC News, 26 June) as a result of the BBC’s analysis. Both Stephen’s father and his best friend are now calling for the criminal investigation into his murder to be reopened (The Guardian, 26 June).

Meanwhile, the Met commissioner, Sir Mark ‘more trust, less crime, high standards’ Rowley – who is still under fire for refusing to accept the term ‘institutional racism’, which first came into public discourse following the 1999 publication of the inquiry into Stephen’s murder – threw a strop over questions asked by ITV journalist Sam Holder at the unveiling of the newly refurbished Tottenham police station (ITV, 21 June). At the reopening (which was definitely, absolutely, unquestionably NOT just a PR exercise for the Met), protestors could be seen holding placards and heard shouting ‘Why won’t you admit that the police force is institutionally racist?’ while a smiling Rowley cut the ribbon across the station entrance. In an interview filmed at the event, Holder asked the commissioner if there were any updates on the force’s internal misconduct inquiries. ‘Oh come on!’ Rowley responds. ‘We’re not going to start there, we’re not going to start on misconduct, that’s […] no, you won’t get anything out of me on it’. In the clip, Rowley then goes on to say: ‘We’re here today for some good news about a local police station being re-opened […] I’m interested in your [Holder’s] questions […] you seem to have turned up as a journalist and you don’t care about a good news story […] Listen, today’s about celebrating’.

We’re no PR experts, but we can confidently say that when a journalist asks a valid and important question about a serious topic, throwing a tantrum because you think the nasty journalist has ruined your special event doesn’t exactly make you look like the kind of respectful, responsive, and accountable commissioner who might be capable of turning the force around. Responding to the video, artist and activist Marlon Kameka (who was at the Tottenham protest) said ‘[Rowley’s response is] a clear sign that this man lacks empathy for victims of misogyny, racism, and homophobia. I guess no amount of media training can cover up a person’s bigotry’.

But we already knew Rowley was sensitive to what he perceives as ‘criticism’, but what anyone else would fairly call ‘accountability and transparency’: during his commissionership he has more than once accused the media of fuelling public distrust in the police by focusing on police failures and misconduct, rather than on police ‘successes’ (one might reasonably assume that this is in large part because there are so few of the latter kind of story to report). The same month he took up the top job at the Met, he wrote on LinkedIn: ‘I find myself considering the role of the media, holding us to account when we get it wrong and also recognising the nuance, the complexity of things and not simply jumping for a headline’.

To top things off this month, English and Welsh police forces’ major anti-racism initiative is now facing accusations of racism by its own staff (BBC, 31 May). The National Police Race Action Plan (NPRAP), which we wrote about in last month’s newsletter (May 2023: Lies, lies, and more lies), received ‘complaints from people from ethnic minorities involved with the programme, with some questioning the credibility of the plan and its true intentions’, according to the BBC. ‘Some [minority ethnic staff] said they had felt their negative experiences were discounted because there was a desire to remain positive.’ This seems to mirror Rowley’s preferred approach – and that of the majority of UK police leaders in general: refuse to fully and sincerely acknowledge just how bad things are and why, and then accuse anyone who does of spiteful and counter-productive pessimism.

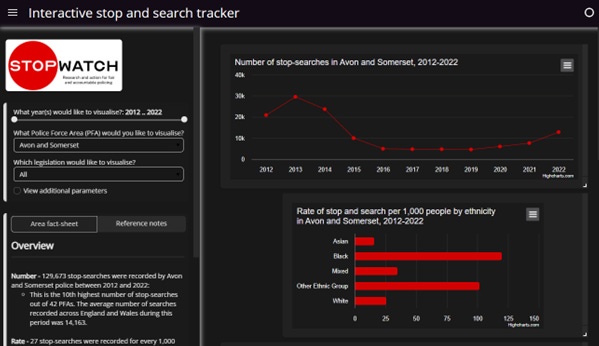

Though Rowley remains personally unwilling to use the term ‘institutional racism’, this month we saw another police chief – this time in Avon and Somerset – publicly recognise institutional racism in her own force, just as the head of Police Scotland did in May (BBC, 16 June). Predictably, as soon as she’d uttered them, chief constable Sarah Crew’s remarks were condemned as ‘virtue signalling’ by Police Federation chairman Mark Loker, who also claimed that the use of the term ‘will create a false narrative’ and that no data exists to support the notion that there is racism in stop and search (Bristol Live, 16 June). If Loker had come out from the rock he’s clearly been living under and taken two minutes to carry out a quick search using StopWatch’s new interactive stop and search tracker, however, he would have known that over the last decade Black people were in fact 4.7 times as likely as white people to be stopped and searched by officers from Avon and Somerset police.

This month at StopWatch, we…

Launched our interactive stop and search dashboard – please check it out and let us know what you think or how you plan to use it. We welcome your feedback!

Attended a dispiritingly unproductive Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC) event held unfortunately (for them) in the immediate aftermath of Suella Braverman’s latest nonsensical statement on stop and search

Tuned into an informative and engaging lecture hosted by Garden Court Chambers on the Public Order Act 2023 – a video recording is available to watch here (our factsheet on the legislation is coming soon)

Have been keeping tabs on the new Serious Violence Reduction Order (SVRO) pilot: the first orders were issued (and also breached) this month in Merseyside (Merseyside police, 13 June)

Topics in this newsletter include:

The home sec’s call for the police to ‘ramp up’ their use of stop and search

The publication of police inspectorate HMICFRS’s annual ‘State of Policing’ assessment and research on the use of section 60 powers

A brief update on the ‘Child Q’ case

Please enjoy our roundup of stories below.

We can see through your ideological games on stop and search, Suella

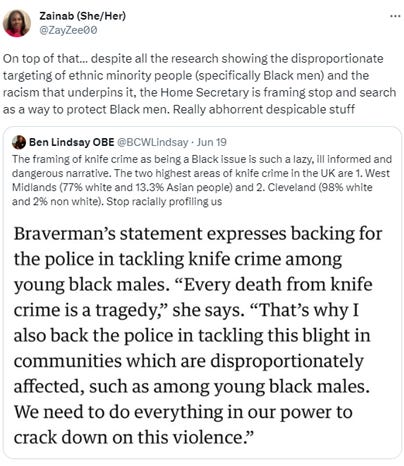

On 20 June, Suella Braverman called on the police forces of England and Wales to ‘ramp up the use of stop and search’ (Home Office, 20 June). ‘Every death from knife crime is a tragedy. That’s why I also back the police in tackling this blight in communities which are disproportionately affected, such as among young black males. We need to do everything in our power to crack down on this violence’, she continued. ‘The Home Secretary has written to chief constables of all 43 police forces in England and Wales, to give her full backing to the common sense policing tactic and to urge them to ensure their officers are prepared to use the full powers at their disposal, so they can be more proactive in preventing violence before it occurs’, said a press release.

Not only are Braverman’s words an embarrassingly transparent ideological move, but in the current social economic context, and when considered alongside the publication of new evidence about section 60 (‘suspicionless’) stop and searches and the policing inspectorate’s annual ‘state of policing’ report, her suggestion that a dramatic increase in stop and search is an infallible and effective way to reduce ‘knife crime’ is simply wrong – and what’s more – she probably knows it.

The policing inspectorate’s report (HMICFRS, 9 June) outlined, as so many similar reports and reviews have also done over the past few months, ‘one of [the police’s] biggest crises in living memory’. ‘I can’t recall a time when the relationship between the police and the public was more strained than it is now’, wrote chief inspector of constabulary Andy Cooke in the report’s introduction. Cooke is supportive of use of stop and search as ‘a valuable tool in the police’s problem-solving toolbox’ (as a former police officer himself, this isn’t surprising), but he does highlight the unacceptably high racial disparities in the police’s use of the power. He goes on to claim that more research is needed to measure the disproportionality and effectiveness of stop and search ‘to fully understand how it affects certain communities and deters crime’.

But several decades’ worth of research and evidence (as well as the lived experiences of those most impacted) has been pretty consistently clear, and the bottom line is that stop and search is disproportionately and often violently used against people of colour, while also being a largely ineffective way of tackling ‘knife crime’ or structural violence more generally. Just a few months ago, Baroness Casey explicitly stated that ‘[e]nough evidence and analysis exists to confidently label stop and search as a racialised tool’ (Casey review, March 2023). And just to give one example of some of the academic work on the power, one prominent analysis of long-term policing and crime data from London failed to find any significant relationship that might suggest that stop and search is effective in detecting or preventing crime. The authors of the study further concluded that it ‘seems likely that S&S has never been particularly effective in controlling crime’ (Tiratelli, Quintin, and Bradford, January 2018, our emphasis). The cross-party political pining for some imagined perfect period in history when stop and search was abundantly and effectively used to keep crime rates low and communities safe thus proves to be an ideological myth, too.

But that hasn’t stopped successive home secretaries since Theresa May’s departure in 2016 gleefully eroding safeguards on stop and search powers. In 2019, Sajid Javid piloted the rollback of the best use of stop and search scheme (BUSSS), removing some of the safeguards around section 60 (s60) searches for some forces. S60 authorisations allow police officers to stop and search anyone within a designated time period and area without the usual need to have reasonable grounds for suspicion. S60 searches also tend to have higher rates of racial disproportionality and lower ‘success’ rates. A few months later, Priti Patel extended the so-called pilot to all police forces in England and Wales (including the British Transport Police), meaning that as of August 2019, s60s could be authorised by more junior ranking officers, for a longer period of time, if the police believed serious violence ‘may’ occur, and without the need to communicate these authorisations to the public in advance.

New research on this ‘pilot’ was published the day before Braverman’s comments were made (Home Office, 19 June). The qualitative component of the research didn’t seek to discover whether or not s60 is an effective tactic in crime reduction terms; instead, it aimed to explore the views of police officers and their perceptions of s60. Worryingly, government endorsements of stop and search powers, along with the removal of s60 safeguards, were felt to be ‘enabling and confidence building’ to police officers – not just in relation to s60, but in such a way that ‘may well bleed into [officers’] confidence in terms of exercising their powers […] elsewhere as well’. ‘Several officers interviewed emphasised just how impactful messaging by chief officers and the Government on the value of [stop and search] was on influencing officers’ views and behaviour “on the ground”’.

The quantitative component of the study gave us a little more insight into how s60 is actually used and whether it’s as effective as Tory politicians and others claim: ‘The vast majority of s60 searches conducted during the pilot period (91%) resulted in ‘no further action’’. Despite Suella’s assertion that stop and search is the best way to detect and tackle ‘knife crime’, a knife was found in just 1% of searches during the ‘pilot’ period. Section 60 authorisations where fewer searches were carried out had a higher ‘success’ rate in terms of outcome (meaning an item was found and the situation was escalated through the system) – but again, we already knew this. The College of Policing’s own guidance openly admits that stop and search ‘tends to be less productive the more the power is used’. We don’t have space here to go into the data tables in depth, but they’re definitely worth taking a look at, too (if you’re so inclined).

In sum, none of this is particularly new. We’ve known for years that one of the primary functions of stop and search is an ideological (rather than a practical) one – especially for the kinds of governments who relentlessly pursue the oppression, criminalisation, and punishment of society’s most marginalised, in both direct and indirect ways. But we’ve got to stop letting them get away with claiming that the answer to ‘knife crime’, or any other kind of serious violence, is simply to ‘ramp up’ the use of stop and search.

Deaths from police contact, cases old and new

Saul Cookson

Saul, 15, was killed when his electric bike crashed into a parked ambulance after being followed by police in Salford, Greater Manchester. The incident has been referred to the IOPC for investigation. (Manchester Evening News, 9 June)

Unnamed (from Middlesbrough)

The IOPC is investigating the death of a 50-year-old man in police custody in Middlesbrough. The man died three hours after being detained and then taken to a custody suite by Cleveland Police officers on the 20th June. (IOPC, 21 June)

Sheku Bayoh

Sheku, 31, died in 2015 after being restrained by six Police Scotland officers. During the ongoing public inquiry into his death, Sheku’s family accused lawyers representing the police of ‘blaming him for his own death’. (The Guardian, 27 June)

Other news

New policing bill unveiled in Scotland: If passed by MSPs, the legislation would see the outcomes of misconduct hearings published online and police officers no longer able to resign to avoid disciplinary proceedings. (Scottish Legal News, 7 June)

Met says it will make public key findings of coronation arrests review: Scotland Yard has said it will make public the key findings of the review, but assistant commissioner Louisa Rolfe declined to say when and defended her officers’ right to make arrests without evidence. (The Guardian, 7 June)

Police who followed boys before fatal Cardiff e-bike crash served misconduct notices: The IOPC said it was examining whether the marked van was chasing Kyrees Sullivan, 16, and Harvey Evans, 15, who were killed moments after CCTV footage caught the police vehicle just behind the bike. (The Guardian, 13 June)

Pressure forces Home Office publish data on police use of powers: The Home Office confirmed it will collate and publish data on the use of police powers to restrict protests, following sustained pressure from Netpol and supporters. (Netpol, 20 June)

Met police officer ‘sorry’ for trauma caused to Child Q: Three years on, Child Q has spoken out for the first time in an updated report into the incident, asking: ‘Why was it me?’. (The Voice, 21 June)

Over twice as many Catholic than Protestant children strip searched by PSNI: Details emerged after the Police Ombudsman published the findings of a report into the ongoing practice. (The Irish News, 27 June)

*Event*

StopWatch newsletter subscribers might be interested in this upcoming event hosted by Healing Justice London on 13 July: ‘Rehearsing Futures Part 2: Experiments in Imagination’.

Section 60 watch*

London

Tower Hamlets (28-29 June)

Wiltshire

Swindon (9 June)

Greater Manchester

3 ‘consecutive’ authorisations in Hulme and Old Trafford (1-4 June), Oldham (5 June, 23 June), Drolysden (10 June), Heaton Park (11 June), Pendleton area of Salford (28 June)

Thames Valley

Milton Keynes (5-7 June; 22 June; 28 June)

* This is not a comprehensive list

Terrible Tech: Met police secretly monitoring kids online

This month in Terrible Tech, we bring you a story about the Met spying on children online. ‘Children as young as 13 have been secretly monitored online as part of a continuing surveillance operation run by the Metropolitan police’, reported Wil Crisp for The Guardian (6 June). The latest revelations about the scheme, called ‘Project Alpha’, have ‘escalated concerns among human rights organisations about the Met potentially violating data laws and disproportionately targeting children from racial minorities’.

Project Alpha was launched in 2019 with the ostensible aim of combatting serious violence partly by scouring social media and reviewing content such as drill music videos. Freedom of information requests submitted by research group Point Source revealed that almost 7,000 records have been created as part of the scheme. According to the Met, each of these records could include data relating to social media account details, online content, age, and ethnicity. ‘Both the Met and the Home Office declined to say what checks and reviews had taken place to make sure that the activities conducted as part of Project Alpha are not racist or discriminatory’, Crisp notes.

The surveillance and monitoring of young people’s social media, as well as the disproportionate focus on drill and rap music videos is even more concerning in light of new research that has uncovered a pattern of police officers being trained as ‘expert witnesses’ on drill and rap music and then being put forward by prosecutors to testify in court against young Black men and boys, often as part of the construction of a ‘gang’ narrative and involving the legal doctrine of joint enterprise (The Guardian, 21 June).

StopWatch is a volunteer led organisation that relies on the generosity of trusts and grant funders to operate. We DO NOT accept funding from the government or police as we believe this would compromise our ability to critically challenge.

We’d appreciate any one-off or regular donations to help support our work. You can click on our Donate button below to go through to our donation page.

—

Stay safe,

StopWatch.